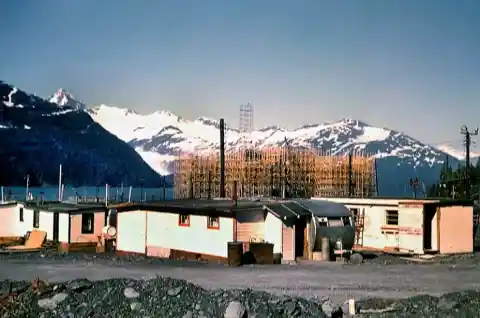

Unexplored Alaska

Alaska continues to be considered one of the last unexplored regions of the North American continent.

As nearly all of its inhabitants are clustered along its southern coast, many people wonder what lies beyond its boundaries.

Alaskan Wilderness

In the last few years, the remote communities of the Alaskan frontier started to spark the interest of the rest of the world.

Many adventurers tried to overcome the Alaskan Bush, but luckily, they only ventured a few miles south of Anchorage.

Large Tunnel

But when you drive 60 miles from the Alaskan capital, you will get to a string of flashing yellow lights.

The road beyond those lights travels only one way, and the traffic may be stuck for a few hours until it changes directions.

Whittier

After the traffic shifts directions, and after a short driving time, you will find yourself in front of a big tunnel that is blocking your path.

There are train tracks coming out of the tunnel that will probably make you wary of entering but don’t worry; this is the only way to go.

Begich Towers

Unfortunately, the tunnel will do little to calm your nerves, and for the next 2.5 miles, you’ll wonder if this was the right choice. Finally, you’ll reach Whittier, a small port community on the shore of Prince William Sound.

Whittier is known as the strangest town in Alaska. The main reason for this comes from the fact that about half of Whittier’s residents live in a single building — Begich Towers.

Sub-Zero Temperatures

Winter weather can be isolating. The cold, the low sun and the occasional snowstorms can make anyone want to stay home and snuggle. But imagine if your whole town had to stay at home in the winter — and in the same building?

That’s how most of the 218 residents of Whittier get through the harshest days of the year: They live and work in Begich Towers, the tallest of the town’s very few structures.

Inside Begich Towers

Rather than face the cold, the people of Whittier built everything they needed inside Begich Towers. There’s a laundromat, med center, church, and convenience store, among many other services.

The whole structure contains condominiums, rental units, city offices, the police department, post office, a mini-market, gym, clinic, pharmacy and the church.

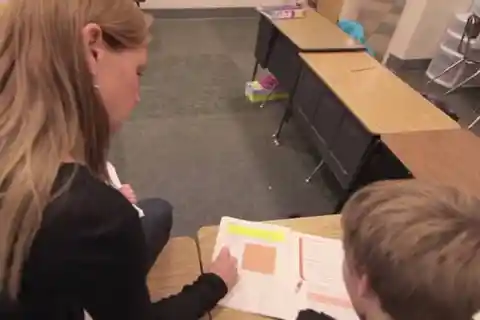

School

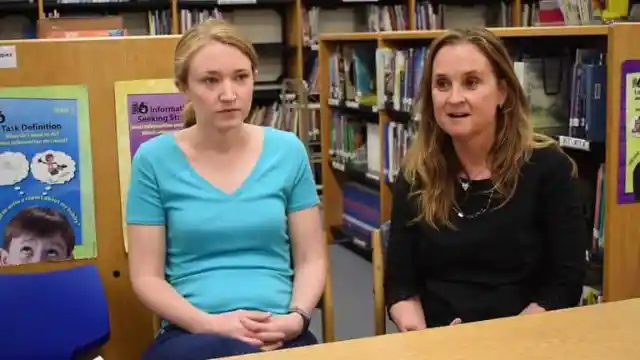

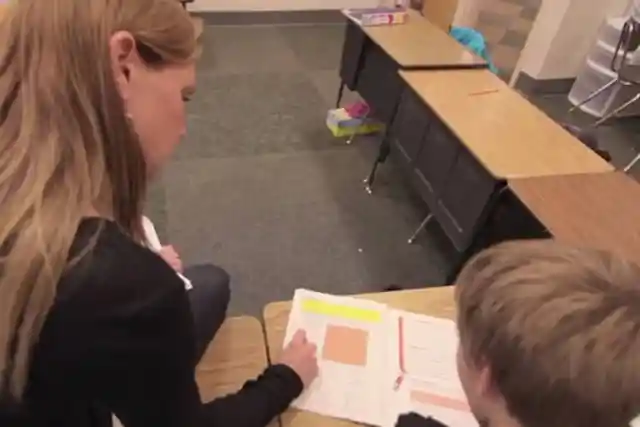

The kids living in Whittier have to go to school at a building attached to Begich by a tunnel due to the strong winds of 60 mph and the quantity of snow that falls each year.

And though most of her students are also her neighbors, teacher Erika Thompson (right) has more or less adjusted to the unusual lifestyle. “For me, it’s just home,” she says. “For the most part, you know everybody. It’s a community under one roof”.

Community

Today roughly 100 people live there, “plus or minus 20”, said Karen Dempster, president of the board of directors of the Begich Towers Condominium Association of Apartment Owners Inc.

The population of Whittier in 2015 was 214.

Indoor Playground

The school includes a large indoor play area; the outdoor playground is covered to shield recess-goers from snow and rain.

Like their parents, the children of Whittier also aren’t fans of the freezing weather, especially when it comes to playing outside. That’s why the town’s only playground is located indoors as well.

Tourist Hotspot

When the sun is out, which occurs 133 days of the year, the scenery is as spectacular as any place in Alaska, and that’s saying something. Summer sunshine lasts for 22 hours a day at Whittier’s latitude, and cruise ships regularly stop in the warmer months with passengers eager to explore.

Every year 700,000 tourists flood Whittier to get a taste of Alaskan life. But there’s only so much to see and do in the small town, and most vacationers are back on their cruise ships by the afternoon.

Small Town

Plenty of folks who stop in Whittier are only in town for a short time — an excursion off a cruise ship, a seasonal job.

But Whittier’s permanent residents have found a way to keep their community spirit year-round and (mostly) under the same roof. Maybe they’re not so isolated after all.

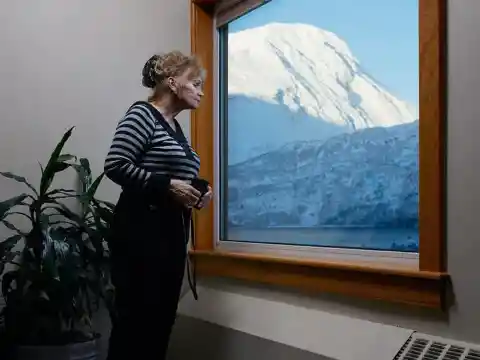

June’s Bed & Breakfast

For those who stay, June Miller is the woman to see. June’s Bed & Breakfast is located on the top of Begich Towers and is the premier accommodation spot. Don’t get startled if she hands you out a pair of binoculars.

“A lot of people keep them there to watch whales breaching and mountain goats grazing and things like that,” photographer Reed Young remarked of his experience at the B&B.

Binoculars

June confessed that the binoculars are actually used “to see if your husband is in the bar.” Well, now you’ve been warned!

There’s no doubt that it takes a special kind of person to visit a place like this, let alone live there.

Perfect Place

According to Erika Thompson, Whittier is the perfect place for everyone, regardless of the lifestyle you prefer. “Some people love it because it can be really social,” she says. “And some people love it because it can be reclusive.”

According to June Miller, a year-round Whittier resident who lives in the tower and runs a vacation rental business on the tower’s top two floors, says that coming back to the tower in the wintertime is an exercise in re-connection.

Free Residents

The appeal of Whittier comes from the fact that the residents here are free to be themselves.

Whittier is a seasonal town, accessible by boat in the summer or on land year-round via a single two-and-a-half-mile tunnel under Maynard Mountain. That tunnel works on a rotational basis, running one direction only, switching every half hour, and closing for the night at about 11 p.m.

Nonexistent Economic Growth

Despite heavy seasonal tourism and a foothold in the commercial freight and fishing industries, economic growth is nonexistent here. With more people leaving the town each year, Whittier’s future appears uncertain.

Though Whittier has a couple of convenience stores, including one right in Begich Towers, the selection is small and prices can be steep. A can of Chef Boyardee spaghetti and meatballs that costs $1.25 in Anchorage is priced at $3.50 in Whittier.

City Manager

“I don’t know where Whittier is going,” the city manager told Young. “Because I don’t know where it wants to go.” The crowds depart, and most of the restaurants and tourist businesses close down.

As the building approached its 60th year, several crises loomed that threatened to make the place uninhabitable and potentially unrestorable.

Trouble in Paradise

First and foremost were the boilers. When the military ran the place, all buildings were served by a single heating plant. When the Army pulled out, each building had to get its own system.

Begich Towers had a pair of boilers in a side building. As of last year, only one was running, and the survivor was experiencing major problems nearly every day.

Panicked

“We were in trouble,” said Dan Johnson, general manager of the building. The boilers moved hot water through the pipes that heated the building, not glycol, the stuff that keeps anti-freeze from freezing.

If they quit working, eventually the water would freeze, and the pipes would burst”. In addition to the heating pipes, the metal inflow and outflow pipes were becoming invalids, choked by accumulating calcium and iron that was as hard as a rock

Water

Johnson showed a one-inch pipe choked down to an opening that would barely accommodate a sewing needle.

Not having water coming out of faucets was frightening enough, but what really gave Dempster the willies was that the sewage system stood on the brink of failure.

Exterior Paint

Other problems included the battered exterior paint. “That’s not just a cosmetic thing,” said Johnson. “The wind here drives the rain into the cinder blocks,” which make up the exterior siding. They also cause the window frames to deteriorate and leak.

Funding for repairs finally came with a $3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dempster, whose credentials include having a law degree, said the paperwork was as daunting as anything she’d ever encountered, but the USDA staff was exceptionally helpful.

USDA

Dempster said that the USDA kept saying, “There’s this one more thing, but don’t worry, we’ll show you what to do.” When the final paperwork was supposed to be delivered, they told me I had to bring it in wearing a pink tutu.

The grant was approved in September 2015, and work began in January. The old boilers were carted out, replaced by three modern models in July. This was the most expensive part of the project.

Old Sewer Pipes

Crews have been replacing corroded iron pipes with PVC. Old sewer pipes are being dug up, which isn’t easy since they lie under the concrete floor of the basement, and no one is exactly sure where they were.

The outside is getting a fresh coat of paint (a project that was estimated to finish in 2018, but they are still working on it), covering the monotone tan with a three-color blue, salmon and beige color.

Upgrades

The upgrades have brought cost savings. Dempster said fuel for the old boilers costs $12,000 a year. The new ones should bring that down to $5,000.

Switching incandescent lights to LEDs and other energy improvements should drop the cost of electricity for the building from $11,000 a year to $8,000.

Additional Upgrades

Additional upgrades include hazmat abatement, removing old asbestos tile flooring and replacing it with a rubberized surface that looks like marble, improving the air exchange system and floating the walls that are covering the cinder block walls of the interior hallways to create a less institutional look and make it easier to paint the surfaces with new colors.

Dempster is serious in her disdain of the military color schemes. Doors were previously a light brown mud color. Now the doors on each floor are consistent and, to Dempster, a more agreeable color, like dark green, burgundy or blue.

Additional Problems

Though the bins outside the towers are supposedly bear-proof and a metal door shuts off the trash room, the bears hang out with hopes of finding an easy meal. Custodians have learned to bang on the door before opening it and to be prepared to shut it quickly if a bold bear isn’t scared off.

A bulletin board at the main entry advertises jobs available in Whittier. Early this month, they included a waitress and assistant city manager. The bulletin board also lists units for rent. A studio goes for $650 a month, $1,000 will get you a three-bedroom unit.

Basement

The basement contains storage cages familiar to condominium dwellers everywhere and a room full of chest freezers, something of a necessity in a town where much food is caught in the ocean and even more is bought in bulk during runs into Anchorage.

The basement also has the town church, a non-denominational affair. It also used to hold the town swimming pool, a feature much-noted in newspaper reports from the 1950s and ’60s. However, the reports failed to mention that it was more like a giant livestock trough.

Celebrating Survival

Whittier will celebrate the building’s upgrades on August 22, even though the paint job isn’t done and other work will be ongoing. New signs are being erected, and a bronze plaque with the building’s original name, the Hodge Building, will be installed.

The repairs should keep the building habitable for some time to come. The structure seems solid enough. A 40-foot tidal wave hit the port during the Good Friday Earthquake in 1964, killing 13 people. But the building suffered relatively little damage.

Buckner Building

They are three separated buildings by gaps the size of a hand that is covered over with material that bends or can be easily replaced after snapping. The design lets the three segments sway independently. But, like all the buildings in the north, it’s one that takes constant attention.

A potent example of what happens when even the most solid construction is neglected can be seen from the windows of half the units in Begich Tower: the Buckner Building, a concrete sarcophagus from the Cold War. The contrast between the Buckner and Begich facilities couldn’t be starker. No one is more aware of the situation than the denizens of the towers.